“Death, in particular, seems to provide … a greater fund of innocent amusement than any other subject.”

~ Dorothy L. Sayers

“It was a dark and stormy night …”

~ Edward Bulwer-Lytton

For me, there’s nothing better on a dark and stormy night or a rainy afternoon than a cup of tea by the fire and a dead body in the library—the fictional variety, of course. In other words, I love a good murder mystery. It’s not the gore or lifeless corpses that draw me in, although a bloodstained axe or Axminster make excellent clues. I’m there for the mystery. Give me a plot that thickens—plenty of twists and turns and the promise of a solution in the end.

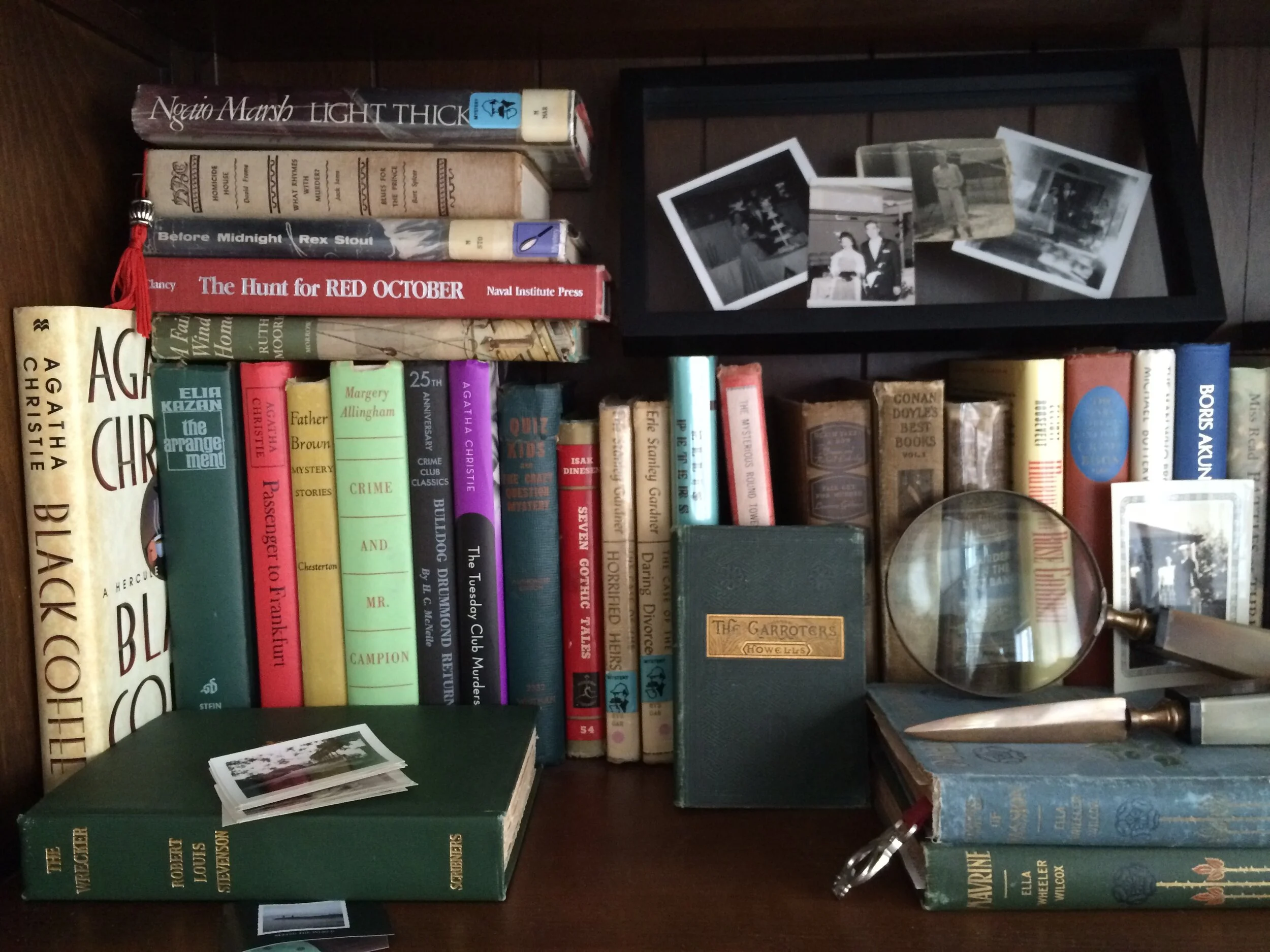

Some of the first grown-up books I read were Agatha Christie mysteries, passed down to me by my mom. I worked my way through the entire Christie canon (more than once) and soon discovered other mystery writers from the Golden Age of crime fiction, Dorothy Sayers, Ngaio Marsh, Margery Allingham, and more. The classic whodunnit remains my favorite literary genre.

While contemplating my possibly morbid reading habits and the abundance of murder-centric stories on my shelves, I’ve come to the conclusion that my affinity for mysteries is not a fixation on death but a desire to make sense of life. A murder puzzle presents a deadly event in a prosaic setting, a trail of clues, and the reassurance that someone is at work to solve the mystery, reveal the culprit, and make everything right in the end. With that reassurance, I can endure even a gruesome murder—as long as it is not my own—and look forward to the unraveling.

“Detective stories contain a dream of justice,” Dorothy L. Sayer’s sleuth, Peter Wimsey says in Thrones, Dominations. “Detective stories keep alive a view of the world which ought to be true. Of course, people read them for fun, for diversion … but underneath they feed a hunger for justice, and heaven help us if ordinary people cease to feel that.”

In this meta moment, the fictional detective acknowledges the real-life purpose of the literary world he inhabits. As murder mysteries bring order and justice to a fictional world, they remind us there is a true north in the real world and a reason to set our bearings on it.

The mythic elements of mystery stories embody archetypes of humanity—and even faith. There is injustice, wrong, chaos and death; people ensnared by circumstances, lost in confusion. There is someone who saves them—sometimes from themselves—by revealing the truth. Someone who condemns the evil, vindicates the innocent, and turns all confusion into a coherent narrative that begins: “The mystery is solved …”

Cue the thunder.

Terri Barnes is a writer, book editor, and book lover. She is the author of Spouse Calls: Messages from a Military Life.

“No, the wisdom we speak of is the mystery of God … That is what the Scriptures mean when they say,

‘No eye has seen, no ear has heard,

and no mind has imagined

what God has prepared

for those who love him.’”

I Cor. 2:7-10